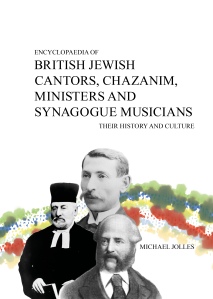

Encyclopaedia of British Jewish Cantors, Chazanim, Ministers and Synagogue Musicians: Their History and Culture. Michael Jolles. London: Jolles Publications. 2021.

Reviewed by Judith S. Pinnolis

Without question, this monumental work of nearly 900 pages (and growing) is a vast achievement and watershed moment in the history of Jewish music in the United Kingdom. The volume gathers and documents a vast historical record in a single compendium. Historian Michael Jolles has created an unparalleled resource available to anyone with an internet connection. While supported by an editorial board, the work displays the views and perspective of a single individual, which Jolles has dubbed a “framework” for the study of British chazanim (the religious prayer leader), synagogue musicians, and institutions. The work also includes lists of rabbis, composers and others contributing to synagogue music. The detailed facts and figures collected represent an amalgamation from myriad archival and research resources into an organized collection. The volume is organized in two main parts. The first describes the roles of the various musicians of the synagogue and the attending historical and cultural backgrounds, which serve as introductory materials, and the second consists of a collection of biographical sketches of various lengths and depths, which date from names known as early as 1656 up to the present.

The primary strength of this volume is its comprehensive nature and collection of known facts; the primary weaknesses are the uneven nature of the biographical facts, the lack of a comprehensive index, and somewhat uneven use of citations and bibliography of sources. Presumably, in the future, a digital version may solve issues of reading the work as a PDF, either printed or on screen. Additionally, the author clearly understands that the work of a single person cannot be as comprehensively complete as desired, and “there is still much relevant information to add” (31) and welcomes future additions, corrections, and recommendations. A section of “precision and impediments to research” clearly states areas where scholars can be aware of possible problems, and notes especially the limits and reliability issues of his sources.

Thoughtfully included is a glossary of common musical, Hebrew, or synagogue words that may need explanation to a lay reader, as well as a comprehensive attempt to define the various distinctions between each term used for a cantor, such as precentor, sheliach tzibbur, baal keriah, baal tefillah and the like. This is followed by several additions around the terms with reference to foreign terms for chazan, lexicographical history, and orthographic preference explanations.

One very interesting aspect of the Encyclopaedia is the selection of descriptive articles on the nature of the job of chazanand all the roles musical and prayer leaders have had in the UK. While this history is done with a broad stroke, the author does give ample primary examples in quotation, making it easy to compare this section to sociological studies of the lives of chazanim such as those Mark Slobin did in his 1987 book, Chosen Voices. [1]

Another interesting aspect of the work that might at first seem somewhat out of scope to a modern frame of mind is the inclusion of rabbis and ministers as well as chazanim. There seems to have been quite an overlap of roles between rabbis and chazanim, and so the listings of all the rabbis are included based on published works from the early 20th century. For the same reason, there are listings of the shochetim (ritual slaughters), and mohelim (ritual circumcizers). Jolles used primary sources, such as advertisements, to show that congregations often expected the chazan to have multiple ritual and synagogue roles and perform a wide range of duties, as well as sing beautifully.

Not leaving anything to imagination on this, Jolles includes an entire section devoted to aspects of the role, including such clarifications as length of appointments, secular activities, observance levels, chaplaincy, and contractual obligations, issues and duties, and the relationship with the rabbi. This is followed by a discussion on the ideal attributes of a chazan, spelled out in full, as in this example, from the 1913 installation of Rev. Abraham Katz at the Great Synagogue:

[1] be blameless in character; [2] be humble in his ways; [3] be simple in his habits; [4] be neat in his attire; [5] be punctual in his duties; [6] be attentive to his work; [7] be among the first to enter the synagogue and among the last to leave; [8] render the service so that it is intelligent and devout, reverential and inspiring; [9] be ever conscious that his task is a sacred one; [10] possess an agreeable voice; [11] be knowledgeable of the Torah; [12] possess an appreciation of the spirit and the soul of the prayers he intones; [13] realise before whom he stands [Berachot 28b] and to whom he prays; [14] not look about him to watch the impression his singing has made, nor shake his hands restlessly and indecorously; [15] in praying aloud, articulate each word and pronounce it correctly; [16] ensure his delivery is quiet, distinct, and in accordance with the sense: whilst indulging in impromptu outpourings of the heart, he must check the desire for too much display, which would unduly prolong the service; [17] not introduce non-Jewish tunes; [18] strive to ingratiate himself to the whole congregation, and not meddle in disputes; [19] be considerate and tactful; [20] in effect, endeavour to become the favourite of the Congregation; and [21] participate in works of charity. (68)

Jolles also includes brief sketches for the music of the cycle of the services and overviews of the various services, prayerbooks and so on. While all this information can be found elsewhere, he always brings it back to British cantors, and some unique quality that he felt needed explanation or inclusion. The detail level is down to the specific synagogue practices that are unique to the United Kingdom, such as a prayer for the royal family. He then embarks on a brief historical tour, starting with Babylonian synagogues and ending with Shlomo Carlebach. While again, there are other surveys, his are always linked back into British particulars, giving his historical essays a unique view; this understanding and philosophical perspective is quite valuable to those who reside outside of the United Kingdom.

Of additional close interest are his essays on the “state of the cantorate” in 1966 and 2009, followed by a timeline of foreign cantors visiting and singing in Britain. This type of listing may be unique, as I don’t think there exists an equivalent for any other country. Jolles’s interests in the immigrant/emigrant aspect of the cantors show that international connections played as much of a role in the development of British Jewry as all other Jewish communities in the world.

Jolles argues for the inclusion of cantorial musical history in the general musical history of Britain, aware that scholars of Jewish music have difficulties being included in any aspect of overall musical history. He includes a section on overall Jewish musical activity in Britain such as classical music—an attempt at such a compilation would not be possible in a single work elsewhere. It seems unlikely that this is even remotely comprehensive, but it does present a number of complex issues regarding the inclusion of Jewish performers of instruments along with cantors as part of the musical picture of a Jewish cultural community. However, this section seems out of scope to the purposes of the volume, and possibly should be included elsewhere or in another book.

Of interest to scholars and librarians will be the catalog of British printed publications on the cantorate. Some are well known while others are, again, specific to the British locale. Those works, many of which were no doubt consulted in the creation of this volume, are of significant interest to Jewish musicologists. Possibly unique to a work such as this is the timeline crafted of significant events in the history of chazzanut, starting in 933 CE. The timeline includes citations for the sources, which this reviewer finds will likely prove highly practical to future scholars. This is followed by several extensive sections on all the synagogues of the United Kingdom, including congregations past and present, essentially comprising a unique directory.

In summary, the introductory materials thoroughly assess all aspects of Jewish liturgical musicians, music, and the institutions of the UK. This includes the various denominations, historical materials, geographical diversity, and social and cultural connections.

The Encyclopaedia then moves to a very large section of biographical and general entries comprising the bulk of the volume. Of great significance are the approximately 2,000 biographical sketches and the additional extensive non-biographical entries, which describe places, synagogues, topics and terms, groups and organizations. An impressive amount of material has been amassed and organized from sources as wide ranging as gravestones and burial records to synagogue brochures and newspaper ads. While these entries are uneven in length–some are just a few lines–each entry includes as much information as possible found in over a decade of research. This section of the Encyclopaedia serves not only as a biographical resource, but de facto memorializes the hundreds of cantors who have served throughout Britain, even if only minimal data was found or is extant. It may be that future scholars will be able to fill in some of the historical gaps on many of the named individuals and institutions in these sections; they will certainly be able to use this Encyclopaedia as a foundational work upon which to build future scholarship.

In a modern twist, the entire work is open access and can be downloaded by writing to DownloadJollesEncyclopaedia@cantors.eu. Jolles also invites crowd-sourcing by welcoming users to contribute to the future growth by submitting suggestions, corrections, images or additions to: EditorialJollesEncyclopaedia@cantors.eu.

Overall, it is little less than astounding to have this vast amount of historical material made available by the dedication of one person. Undoubtedly, Jolles will continue to receive well-earned acclaim and thanks for this ambitious undertaking. He has set the table, now it is for future scholars to come and use it and build upon it.

Judith S. Pinnolis is Associate Director of the Berklee College Library where she produces the series “Books@Berklee.” Previously, she worked at Brandeis for over two decades. She is Vice-Chair of NEMLA (New England Music Library Association). She chaired the Jewish Music Roundtable of the Music Library Association for 13 years; served as Chair of Chapters Council of ACRL; and President for ACRL/New England Chapter. She has contributed to The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Music Studies; Basic Music Library: Essential Scores and Sound Recordings, 4th Edition; Encyclopedia Judaica; Women and Music in America Since 1900: An Encyclopedia; and The Reader’s Guide to Judaism. Her articles include: “’Cantor Soprano’ Julie Rosewald: The Musical Career of a Jewish American ‘New Woman'” in The American Jewish Archives Journal.

[1] Mark Slobin. Chosen Voices: The Story of the American Cantorate (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1989).

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article