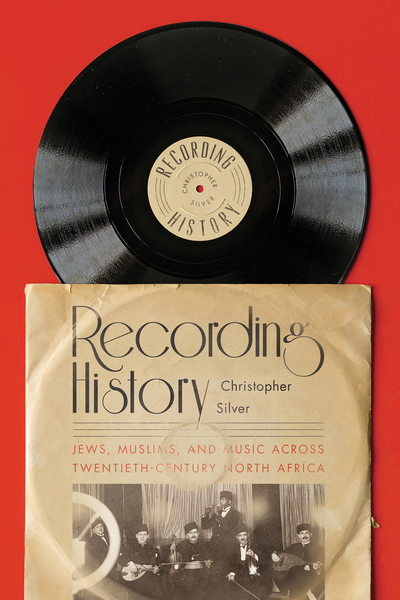

Recording History: Jews, Muslims, and Music across Twentieth-Century North Africa. Christopher Silver. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 2022.

Reviewed by Hugo Hadji

In Recording History: Jews, Muslims, and Music across Twentieth-Century North Africa, Christopher Silver provides the first in-depth and comprehensive history of the North African music recording industry and scene from the dawn of the twentieth century to the early post-independence era. Guided by the premise that music and history are mutually constitutive, Silver offers to listen to the sounds and artists that shaped and reflected the identities of Jews and Muslims living in the Maghreb region during that period. Such work, Silver convincingly argues, “provides twentieth-century North Africa with a soundscape that dramatically alters its historiographical landscape” (13) and allows us to use music to explore Jewish-Muslim relationships, coexistence, and subjectivities outside of and challenging the typical frameworks of “majority-minority” power relations and the mass departure of Jews in the 1950s and 1960s dominant in the literature. It further allows us to acknowledge and recount the central place Jews held in the construction and development of the recording industry and popular musical scene in North Africa, as artists and as intermediaries.

Silver employs a variety of sources ranging from personal interviews, oral histories and archives to radio broadcasts, memoirs, and photographs. Of particular importance, the book takes the reader on a journey that follows the lives and trajectories of shellac discs, one of the most decisive technological innovations of the first half of the twentieth century. Throughout the book, Silver showcases the central role these musical objects and the grooves they contain played in sounding and constructing changing North African societies from colonial times to post-independences. Following the discs’ paths, Silver highlights the place of the Maghreb region in a transnational and global industry of commercial recordings of popular music. He further sounds complex connections and routes of people and objects between North Africa and various parts of the world with a primary focus on France and Israel. The book thus inscribes itself in the growing literature that recognizes the importance of accounting for aural, popular, and mass culture in our understanding of the MENA region. [1]

The book comprises six chapters that explore various topics within the North African music scene and industry. Chronologically, Silver follows the journeys of artists, songs, and shellac discs that have shaped and defined the soundscape of Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco from the colonial period to the late 1960s. The first chapter delves into the life of Edmond Nathan Yafil, the famous Algerian Jew of working-class background born in Algiers in 1874. Silver unpacks his central role in the Algerian music scene beyond his work in the early twentieth-century revival movement of Andalusian music, a frame that has been the primary focus of existing literature. Notably, the chapter details how Yafil played a critical role in the development and popularization of the phonograph and recording industry in Algeria in the early 1900s, recording and collaborating with many artists both Jewish and Muslims, but also acting as a consultant and artistic director to major labels. Through the figure of Yafil, the chapter not only traces the development of the burgeoning recording industry in the Maghreb region, but also highlights the centrality of Jews as artists, entrepreneurs, and representatives in its growth. Moreover, Silver convincingly argues that a class reading and a turn to music render audible the productive relationships between Muslims and Jews during the interwar period, dynamics that have often been masked by the emphasis on the different social and legal statuses given to Muslims and Jews under French colonial rule.

The second chapter opens with a brief overview of the development of Yafil’s orchestra El Moutribia during the interwar period. Silver details the changes in size and composition of the ensemble with the addition of Muslim artists such as the tenor Mahieddine Bachtarzi, and also the addition of popular music genres, belly dancing, and theater performance to the ensemble that had previously solely performed Andalusian music. This concise introduction leads to the core of the chapter, which follows the lives and works of four Tunisian Jewish female stars, Habiba Messika, Ratiba Chamia, Louisa Tounsia, and Dalila Taliana, as well as their Jewish male composers who, for the most part, came from theater. The chapter shows that through their popular music, setting subversive and salacious lyrics in colloquial Arabic to Foxtrot and Charleston grooves, these female superstars “captured a certain-working class encounter with colonial modernity that was as true for the urban Jewish masses as it was for their Muslim counterparts” (47), one that challenged gender norms and sounded new conceptions of the nation and the role of women during the interwar period, thus accompanying the emerging feminist movements in North Africa.

The third chapter delves into another part of these female (and male) superstars’ repertoire, that of sounding the growing and complex nationalist, anti-colonial, and reform-oriented movements and sentiments of the interwar period in the Maghreb region. Once again, Silver invites the reader to go back to the shellac discs and follow the distribution in Morocco of three discs recorded by Habiba Messika and the two Algerian Jews Lili Labassi and Salim Halali. The chapter highlights transnational networks of artists, discs, and grooves that sounded and shaped a palette of nationalisms in the region. Silver demonstrates the power of music in shaping new ideas of the nation and details the French colonial authorities’ attempts at controlling and censoring shellac discs. Of particular importance, the chapter shows that Jewish-Muslims relationships and collaborations in the production and consumption of music was particularly thriving during the interwar period, thus offering a counternarrative to one of rupture and static relationships between the two communities. Finally, this chapter, like the previous one, demonstrates that by carefully listening to the sounds of the interwar period, the centrality of historical actors and dynamics often absent in the historiography and literature of the region, namely women, Jews, and their relationships with their Muslim counterparts, are rendered audible and visible in the production of the era’s soundtrack.

Chapter four assesses how World War II drastically altered the North African music scene and recording industry, dictating who and what could be listened to, performed, recorded, and broadcast. The chapter starts with an analysis of the “battle of the airwaves” in the Maghreb region between France, Italy, and Germany in the years leading to the war. Silver delves into the different strategies employed, music, and programs aired with a special focus on Radio Tunis and the Hebrew Hour, the first Jewish radio program in the Maghreb. The bulk of the chapter analyses how Jewish musicians suffered from and responded to the antisemitic laws promulgated by the Vichy regime in the Maghreb and in occupied France. Silver further analyzes the ambivalent positions of Muslims toward their Jewish counterparts during the period, with some like Bachtarzi singing praises of Pétain. Silver showcases how “the quieting of Jewish musicians who had largely dominated the North African recording industry and concert scene until World War II, created openings, opportunities, and new realities for their Muslim peers which would carry into the postwar period” (106). Finally, the chapter documents the arrival of the American army in North Africa in 1942 and details the contrasting reactions of the population, once again by listening to the sonic experiences and narratives embedded on shellac discs.

In chapter five, by listening to the most prominent Moroccan voice of the era, Samy Elmaghribi, Silver convincingly (re)considers the historiography of Moroccan independence accounting for the Jewish involvement in nationalist movements often absent in the scholarship. The chapter follows the life and work of this Jewish artist, closely detailing his background and debut in 1947, his national and international celebrity in the 1950s, his friendship with the Moroccan Sultan Mohamed Ben Youssef and the royal family, and the establishment and running of his label Samyphone. Silver analyzes Elmaghribi’s songs, discs, and business, locating them it in the tumultuous political context of the period, in-between independence movements, the rise of antisemitic violence, the establishment of the state of Israel, and the start of the outmigration of North African Jews to France, Israel, and North America. The strength of the chapter lies in its ability to explore how in this context, Elmaghribi, and other Jewish artists like Salim Halali in Algeria or Raoul Journo in Tunisia, were pivotal in the spread of nationalist and patriotic messages in their music and concerts. The chapter shows how Elmaghribi brought Muslims and Jews together by shaping a Moroccan national sound that not only resonated in the country but in neighboring Algeria during its war of independence.

The final chapter of the book proposes a different narrative to the unidirectional frame of Jewish departures of the 1950s and 1960s common in the literature. Via careful listening to songs and rumors circulating among the Maghrebi Muslim population about the whereabouts of famous Jewish musicians such as Elmaghribi, the chapter concerns the “living memories of Jews in North Africa at the moment of their curtain call” (173). Silver explores Elmaghribi’s running of his transnational label Samyphone as well as the lives and careers of Jewish musicians in the 1950s and 1960s in-between North Africa, France, and Israel, and their relationships with their Muslim counterparts. It shows that, while most Jews left the Maghreb region during these two decades, not all did, and that the ones who stayed continued to play a central role in shaping the Maghrebi soundscapes in the years leading to independence and early post-colonial North African societies. Moreover, the chapter demonstrates that North African Jews maintained connections to their homelands even after departure, with music and discs once again playing an important role.

Recording History is a well-written and compelling book. Silver meticulously narrates the rich stories of artists and songs and contextualizes them in the social, political, and economic contexts of their times. The major achievement of the book rests in its perpetual emphasis on its thesis. Through each chapter, Silver invites the reader to go back to the shellac discs and listen to the various grooves that made up the soundscapes of the Maghreb region and demonstrates the role of music as a medium for sounding and shaping complex individual and collective identities that surpassed political, ethnic, linguistic, and religious categories. Silver proposes a convincing and more nuanced history of twentieth-century North Africa that listens to the complexities of North African societies and cultures, and frames Jewish-Muslim relationships “through lenses of entanglement and enmeshment” (14). In sum, with Recording History, Christopher Silver offers an important contribution to a range of fields from Jewish, Sephardic, Middle Eastern, and North African Studies, to history, ethnomusicology, and popular and North African Music Studies.

Hugo Hadji, SOAS University of London

[1] See Walter Armbrust, Mass Culture and Modernism in Egypt (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press 1996); Marc Schade-Poulsen, Men and Popular Music in Algeria: The Social Significance of Raï (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1999); Charles Hirschkind, The Ethical Soundscape: Cassette Sermons and Islamic Counterpublics (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2006); Cristina Moreno-Almeida, Rap Beyond Resistance: Staging Power in Contemporary Morocco (London: Palgrave McMillan, 2017); Ziad Fahmy, Street Sounds: Listening to Everyday Life in Egypt (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2020); Andrew Simon, Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2022); and Hanan Hammad, Unknown Past: Layla Murad, the Jewish-Muslim Star of Egypt (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2022).

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article