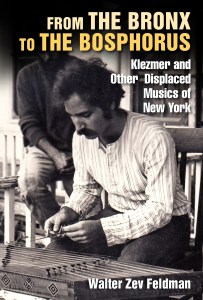

From the Bronx to the Bosphorus: Klezmer and Other Displaced Musics of New York. Walter Zev Feldman. New York: Fordham University Press. 2025.

Reviewed by Yale Strom

Walter Zev Feldman’s From the Bronx to the Bosphorus (2025) is a hybrid work of memoir and cultural history that documents both the author’s personal trajectory and the diasporic musical traditions that shaped his career as a performer and scholar. The book does not conform to the structure of a conventional academic monograph; instead, Feldman weaves a richly layered narrative tracing his family roots, his musical education, and the many diasporic traditions he encountered in New York from the 1950s through the 1990s. During this period, immigrant cafés, clubs, and social gatherings served as vital spaces for the transmission of traditional repertoires, and Feldman positions himself as both participant and chronicler in this world.

Growing up in the Bronx, Feldman immersed himself in a dazzling array of musical environments that overlapped and intersected in surprising ways. He engaged deeply with Armenian music, the folk traditions of the Caucasus, Greek urban styles, klezmer, Persian classical music, Romani repertoires, and other East European genres. Each chapter illustrates not only the extraordinary diversity of New York’s immigrant soundscape but also Feldman’s determination to learn directly from master musicians in their own communities. His memoir reminds the reader that mid-twentieth-century New York was not only a hub of jazz and popular music but also an unparalleled laboratory for diasporic folk traditions, where sounds and practices from multiple continents coexisted and influenced one another.

Feldman grew up the child of Bessarabian Jewish immigrants and was especially influenced by his father, who exposed him at an early age to folk songs from Bessarabia and the prayer melodies of the neighborhood synagogue. This early exposure to both secular and sacred music gave Feldman a remarkably broad foundation as he encountered new traditions. His narrative emphasizes the porous boundaries between genres and the ways in which musicians of different backgrounds engaged in dialogue, collaboration, and mutual influence. In this respect, Feldman’s work echoes the observations of ethnomusicologists such as Bruno Nettl and Mark Slobin, who have long emphasized the fluidity of folk traditions and the importance of intercultural exchange in shaping musical life.

Particularly compelling are Feldman’s detailed recollections of lessons and performances with master musicians, which offer invaluable primary-source testimony to practices that were often under-documented in academic literature of the time. Through these anecdotes, the reader gains insight into the apprenticeship culture of immigrant music communities, where transmission was oral, improvisational, and highly relational. Feldman’s writing captures the tactile, aural, and social dimensions of musical learning, providing a texture often missing from more formal ethnomusicological analyses.

Feldman is now widely recognized as one of the foremost scholars of klezmer music. He situates klezmer within a broader Mediterranean and Middle Eastern musical matrix, like many itinerant folk traditions, noting how modal frameworks predating the Abrahamic religions were adapted and recombined across the Black Sea region. This perspective illuminates how the itinerant musician functioned as a conduit of layered cultural memory, absorbing, blending, and transmitting musical material across ethnic and national boundaries. In this respect, Feldman’s work aligns with Kay Kaufman Shelemay’s [1] explorations of musical migration and memory, highlighting the resilience and adaptability of diasporic repertoires.

Remarkably, when Feldman first began his ethnographic research (eventually he traveled abroad to the places where these folk music genres came from) it never required him to leave New York City. By moving across boroughs—the Bronx, Manhattan, Queens, and Brooklyn—he encountered musicians who shared their experiences of preserving, transforming, or losing their traditions. They often welcomed Feldman’s curiosity, even though he was not from their ethnic community, because many of their own children showed little interest in “archaic” genres amid the dominant pressures of American popular music. Feldman’s engagement thus reflects a form of community-based ethnography, where trust and social embeddedness were essential for meaningful access, echoing Slobin’s emphasis on the ethnographer’s role as both participant and observer.

The book is organized into distinct sections: his formative years in the Bronx; visits to Greek, Armenian, and Turkish cafés and clubs; lessons with celebrated performers who became lifelong mentors; an unexpected interlude in Colorado; and, finally, his introduction to clarinetists Andy Statman and Dave Tarras. These encounters catalyzed his deeper research into klezmer and helped establish him as a central figure in the American klezmer revival of the late twentieth century. Feldman’s memoir provides a rare insider’s perspective on the revival movement, illustrating the interplay between personal passion, apprenticeship, and scholarly rigor.

Methodologically, the book occupies a unique position. It does not conform to standard ethnomusicological monographs, lacking extensive citations, transcriptional analysis, or systematic comparative frameworks. Instead, Feldman relies on autobiographical memory and anecdotal description as primary evidence. This produces a richly textured and highly personal account, but it also raises questions of selectivity and subjectivity. The prominence given to certain musicians reflects Feldman’s own access and relationships, which may unintentionally obscure parallel or competing narratives within the same communities. Yet, this insider approach provides depth of experiential knowledge that purely archival or analytical studies rarely capture, highlighting the value of autoethnography in documenting marginalized or ephemeral musical cultures.

Certain specialized musical terms—makam, specific modes, and instruments—may challenge readers without prior training. Feldman provides glossaries and suggested readings, but sections occasionally assume familiarity with music theory or ethnomusicology. Additionally, his occasional use of the term “Gypsy” rather than “Roma” stands out, given his otherwise careful attention to ethnonyms. As contemporary scholarship and field experience among Roma communities have shown, the term “Gypsy” carries derogatory connotations, reinforcing stereotypes of nomadism and criminality, and its uncritical use is a notable inconsistency in an otherwise conscientious text.

Despite these minor shortcomings, the hybrid form of memoir and ethnography is a central strength. Feldman’s decades-long immersion as both performer and apprentice allows him to document musical practice, pedagogy, and social context with exceptional nuance. His work preserves repertoires and practices endangered by assimilation and generational change, offering rich qualitative data for future researchers. Moreover, the book illustrates how cultural memory, personal biography, and scholarly inquiry can converge in a single text, making it a significant contribution not only to klezmer studies but to the study of transnational musical diasporas more broadly.

From the Bronx to the Bosphorus thus occupies an important place in the literature on diasporic music, bridging personal narrative and ethnographic observation. Feldman’s work demonstrates the enduring value of embodied knowledge and apprenticeship in preserving musical heritage, and it offers a model for how scholars can engage with living traditions without imposing an exclusively academic lens. For readers interested in klezmer, New York’s immigrant soundscape, or the dynamics of musical diasporas, Feldman’s memoir provides both a vivid historical record and a deeply human account of the music that shapes and is shaped by the lives of those who perform it.

Yale Strom (yalestrom.com) is a world-renowned artist/ethnographer who has done extensive field research in Eastern Europe among the Jewish and Romani communities. His research has resulted in books, documentary films, recordings, plays and photo exhibitions that have been seen and heard all over the world. He is the author of “The Absolutely Complete Klezmer Songbook” (Transcontinental Music) and “The Book of Klezmer” (Chicago Review Press). Strom is the leader of the klezmer fusion ensemble Hot Pstromi and is a recording artist on the Naxos/Arc Music UK label.

[1] Kay Kaufman Shelemay, Sing and Sing On: Sentinel Musicians and the Making of the Ethiopian Ethnomusicology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022).

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article