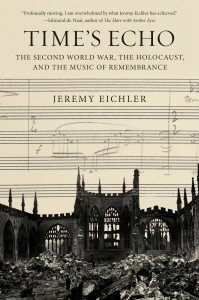

Time’s Echo: The Second World War, the Holocaust, and the Music of Remembrance. Jeremy Eichler. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. 2023.

Reviewed by Karen Painter

Jeremy Eichler makes a passionate case that as we approach a world without living memory of the Holocaust, there is an “ethical imperative” to attend to “musical memorials” which summon “our commitment to witness” (pp. 174–175). Written when Eichler was classical music critic for the Boston Globe, Time’s Echo bears the fruits of his profession everywhere in eloquent and astute description of music that matters deeply to him. A historian who wrote his dissertation on Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw, Eichler undertakes the ambitious task of showing how music became so important to German Jews, which finds him starting his story in the Enlightenment, tracing the ideal of Bildung (cultivation) across Central European history. The book’s subtitle notwithstanding, we arrive at World War II only in chapter four out of ten.

Indifferent to a disciplinary sea-change within both musicology and history, Eichler gives rein to unabashed admiration of four great men. Part 1 focuses on Richard Strauss (end goal: Metamorphosen) and Schoenberg (A Survivor from Warsaw), with observations of other German Jews along the way, from Moses Mendelssohn to Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, from Mahler to Arnold Rosé. The briefer part 2 covers Britten (War Requiem), Shostakovich (Symphony No. 13), and their friendship. Women are absent from the authors, artists, and musicians who supply historical context, with one exception. The broad narrative arc about German-Jewish Bildung leads Eichler to the women’s orchestra in Auschwitz, which Rosé’s daughter Alma conducted for seven months. He notes that “Alma Rosé’s musical nobility, the final flickering of the Bildung ideal, quite literally saved the lives of many orchestra members” (p. 47). A consummate storyteller, Eichler sheds protocol, conjuring up the musician by her first name (p. 200), going so far as to admire her as “savior of lives and keeper of a vision of Bildung long after it had been abandoned by her countrymen” (p. 202). Yet German Jews did not “abandon” Bildung (nor did other Germans, including Nazis); until the Gestapo ordered its closure on September 11, 1941, the Jewish Cultural League offered community programming for the persecuted in numerous German cities.

Eichler understandably sidesteps the use and abuse of classical music in the name of National Socialism, but the promise of Bildung through music was, tragically, relevant to camp administration. Guards who tortured and murdered by day would assuage their conscience at night with private concerts; regular Sunday concerts for the SS offered spiritual renewal. “Orchestras” were ordered to play to muffle screams during gassing and, in a cruel irony, “welcome” the arriving trains of deportees. The light fare of the programming is hard to reconcile with the serious ideals of Bildung, and working conditions included harrowing practices like “music on command” that fed the camp’s power asymmetry. Appointed Kapo, Rosé imposed discipline and strictures that the conductors before and after her did not. The willingness or ability to perform did save lives, though occasionally a musician’s virtuosity projected a confidence that the SS fatally struck down. If fewer died under her tenure (rank speculation), was it due to the orchestra’s “distinction” (p. 47)?

Biographers are hardly to be faulted for idealizing their subject, and Eichler is no exception. I don’t commend Strauss for “never joining the Nazi Party” (p. 84), as his age disqualified him (69 in 1933), and the regime did not expect the most eminent artists to join. Eichler believes that Strauss viewed composing Metamorphosen as his “penance” for Nazi collaboration, citing the composer’s identification with the eponymous character of Guntram, who must seek penance in his own way (pp. 118, 120). The piece may represent Strauss’s escapism, or perhaps desperately seeking to preserve his legacy, but the Christian overlay of penance seems unlikely. Profound empathy also colors the treatment of Schoenberg’s reflections about Jewish identity. Given that the composer was widely known, in years prior, as a monarchist with authoritarian leanings, his 1938 Four-Point Program for Jewry should be read at face value, not (pace Eichler) attributed to his artistic vision (p. 136). On the other hand, I don’t take at face value the statement that by 1947, “as Schoenberg confided to one family member, he had recently suffered more humiliations in the United States than he had during the previous three decades of his life combined” (p. 139). The quotation dates from the intense twelve-day stretch when Schoenberg composed A Survivor from Warsaw in California and heard, through another family member, bad news about his daughter’s health (she would pass four months later in New York). Perhaps ashamed of not having written to her since her surgery, Schoenberg gushed forth one excuse: to earn the requisite income, he’s been frightfully busy; then, realizing that this calculation wouldn’t adequately justify his silence, Schoenberg sought pity from her about the onslaught of “humiliations” he had experienced. Eichler elsewhere writes about Schoenberg’s reference to being “redeemed from thousands of years of humiliation, shame and disgrace” (pp. 42, 145); however, the context is an essay about Schoenberg’s generation, not himself.

Minor infelicities never imperil Eichler’s larger argument. For example, sketching the historical context for Schoenberg’s work on Moses und Aron, Eichler reports on fascist brownshirts demonstrating at new music concerts and quotes a “typical” critique that Schoenberg’s “soul-life has nothing in common with ours” (p. 70)—but the review dates from December 1922 (Alfred Heuß’s criticism of Five Pieces for Orchestra). One can give or take a few years in a sprawling history, except when Eichler presses on the importance of chronology: “Strikingly, Zweig and Strauss created Die schweigsame Frau at precisely the same time that Schoenberg was composing the first two acts of Moses und Aron” (p. 92)—only there was no such overlap. Schoenberg stopped work on his opera in March 1932, and Strauss only received Zweig’s libretto, to set to music, in June 1932; he finished in October 1934.

What may seem to scholars a cavalier treatment of sources and facts is usually inconsequential. Moses Mendelssohn was not “an old man” in the summer of 1780 (p. 29), he was Eichler’s age, 51. Erwin Kern, who assassinated Walter Rathenau, did not later justify the murder “as a kind of rearguard action against the Bildung ideal” (p. 63), since he was inadvertently shot dead by the police two weeks after the assassination. But in Jewish Studies, particularly as a field sidelined in musicology for many years, a lot is at stake. Pace Eichler (p. 41), Wagner’s anti-Semitism did not grow from “biological essentialism”; his essay “Jewishness in Music” exhibited a cultural anti-Semitism that would not be useful to the genetic anti-Semitism of Nazism (Wagner always presumed his Jewish stepfather was his biological father). Holocaust education matters, and so does every last detail. The “yellow Star of David” was not “used to brand . . . individuals” on the April 1, 1933 boycott (p. 128); the yellow star on clothing only became compulsory in 1939.

Sometimes it is merely zesty prose that misleads. We read that Wassily Kandinsky “sent Schoenberg some fan mail” (p. 44)—a colloquialism that belies the reciprocity and depth of their extensive correspondence. Or, “Despite his family’s ancestry, . . . for at least the first six decades of his life [Schoenberg] worshipped at the shrine of Richard Wagner” (p. 40); Wagnerism enchanted many composers around 1900, including those born to Jewish parents (Mahler and Franz Schreker among them). The flippant generalization about Schoenberg may favor style over content. The usual sobriety in scholarship on anti-Semitism is likewise turned askew when Eichler references the Grimm Brothers’ antisemitic tale “The Jew among Brambles” in the chapter title “Dancing in the Thorns,” characterizing Jewish-German musicians who remained active in musical life until Nazi control forced their emigration. Further, Eichler mistakenly idealizes Grimm’s Jew as a martyr who is “hanged in punishment for the servant’s crime” (p. 51); in Grimm, the Jew admits to having stolen the money bag, which he then falsely accuses the servant of stealing from him.

Historically, the language of music criticism has taken stylistic liberties embedded in the biases of its milieu. At the risk of pedantry, the scholar may worry about implications that are inadvertent. At one point, Eichler links the legal emancipation of Jews, Schoenberg “formally leaving his Jewish faith,” and his emancipation of dissonance, adding that dissonance was “‘noise’ that had for centuries been walled off, ghettoized, in a place beyond the boundaries of what was tolerated as good Christian music” (p. 44). Who “ghettoized” dissonance? Even antisemites largely avoided the term “ghetto” in music criticism; the only instance I’ve encountered is eventual Nazi party member Paul Ehlers, who objected to “ghetto rhythm” and “brown timbre” at the Munich premiere of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony.

It’s not entirely clear why Eichler warns the reader that what follows is “a very personal book” (p. 13). For me, the only jarringly personal moments were reading about the sunlight and breathtaking (or drab) environs from Eichler’s site visits where music was inspired, composed, or played. Eichler narrates with perhaps more eloquence than anyone else a historical period of enduring fascination; even experts will encounter new material every few pages, and his vivid description of music is invaluable. As listeners and teachers, musicologists can find no more engaging and relevant book on this gripping period of history; its moments of disappointment pale before the enduring admiration that Eichler possesses the vision, humanity, and prose to attract a broad audience and win the investment of a major publisher for a subject of increased importance in today’s political landscape.

Karen Painter, Professor of Music at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, was previously on the faculty of Harvard University and Dartmouth College. Author of Symphonic Aspirations: German Music and Politics, 1900–1945 and editor of Mahler and His World, Painter has a forthcoming article “Music after Kristallnacht: Cultural reportage in the Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt” in the Dubnow Institute Yearbook.

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article